Prevalence and molecular genetic characteristics of parenteral hepatitis B, C and D viruses in HIV positive persons in the Novosibirsk region

- Authors: Kartashov M.Y.1,2, Svirin K.A.1, Krivosheina E.I.1, Chub E.V.1, Ternovoi V.A.1, Kochneva G.V.1

-

Affiliations:

- State Scientific Center of Virology and Biotechnology “Vector” of the Federal Service for Surveillance of Consumer Rights Protection and Human Welfare (Rospotrebnadzor)

- Novosibirsk National Research State University

- Issue: Vol 67, No 5 (2022)

- Pages: 423-438

- Section: ORIGINAL RESEARCHES

- URL: https://journal-vniispk.ru/0507-4088/article/view/118241

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.36233/0507-4088-133

- ID: 118241

Cite item

Full Text

Abstract

Introduction. Parenteral viral hepatitis (B, C, D) and HIV share modes of transmission and risk groups, in which the probability of infection with two or more of these viruses simultaneously is increased. Mutual worsening of the course of viral infections is important issue that occurs when HIV positive patients are coinfected with parenteral viral hepatitis.

The aim of the study was to determine the prevalence of HCV, HBV and HDV in HIV positive patients in the Novosibirsk region and to give molecular genetic characteristics of their isolates.

Materials and methods. Total 185 blood samples were tested for the presence of total antibodies to HCV, HCV RNA, HBV DNA and HDV RNA. The identified isolates were genotyped by amplification of the NS5B gene fragment for HCV, the polymerase gene for HBV and whole genome for HDV.

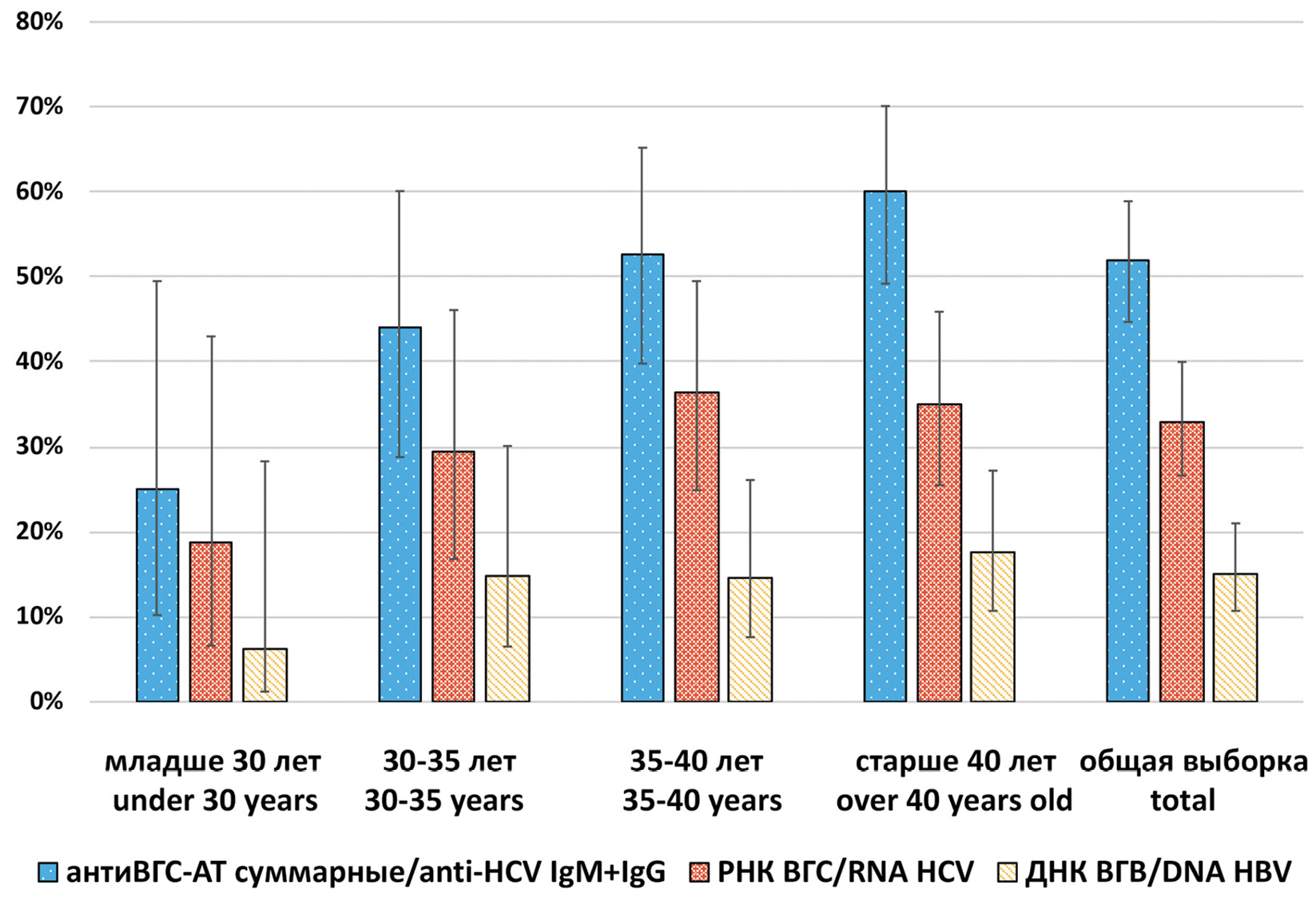

Results. The total antibodies to HCV were detected in 51.9% (95% CI: 44.7–58.9), HCV RNA was detected in 32.9% (95% CI: 26.6–39.5) of 185 studied samples. The distribution of HCV RNA positive cases completely repeated the distribution of HCV serological markers in different sex and age groups. The number of HCV infected among HIV positive patients increases with age. HCV subgenotypes distribution was as follows: 1b (52.5%), 3а (34.5%), 1а (11.5%), 2а (1.5%). 84.3% of detected HCV 1b isolates had C316N mutation associated with resistance to sofosbuvir and dasabuvir. The prevalence of HBV DNA in the studied samples was 15.2% (95% CI: 10.7–21.0). M204I mutation associated with resistance to lamivudine and telbivudine was identified in one HBV isolate. Two HDV isolates that belonged to genotype 1 were detected in HIV/HBV coinfected patients.

Conclusion. The data obtained confirm the higher prevalence of infection with parenteral viral hepatitis among people living with HIV in the Novosibirsk region compared to the general population of that region. The genetic diversity of these viruses among HIV infected individuals is similar to that observed in the general population.

Full Text

##article.viewOnOriginalSite##About the authors

Mikhail Yu. Kartashov

State Scientific Center of Virology and Biotechnology “Vector” of the Federal Service for Surveillance of Consumer Rights Protection and Human Welfare (Rospotrebnadzor); Novosibirsk National Research State University

Author for correspondence.

Email: mikkartash@yandex.ru

ORCID iD: 0000-0002-7857-6822

PhD, MD (Biology), Senior Researcher, Department of Flavivirus Infections

Russian Federation, 630559, Novosibirsk Region, Koltsovo; 630090, NovosibirskKirill A. Svirin

State Scientific Center of Virology and Biotechnology “Vector” of the Federal Service for Surveillance of Consumer Rights Protection and Human Welfare (Rospotrebnadzor)

Email: svirin_ka@vector.nsc.ru

ORCID iD: 0000-0001-9083-1649

Junior Researcher, Department of Flavivirus Infections

Russian Federation, 630559, Novosibirsk Region, KoltsovoEkaterina I. Krivosheina

State Scientific Center of Virology and Biotechnology “Vector” of the Federal Service for Surveillance of Consumer Rights Protection and Human Welfare (Rospotrebnadzor)

Email: katr962@mail.ru

ORCID iD: 0000-0001-5181-0415

Junior Researcher, Department of Flavivirus Infections

Russian Federation, 630559, Novosibirsk Region, KoltsovoElena V. Chub

State Scientific Center of Virology and Biotechnology “Vector” of the Federal Service for Surveillance of Consumer Rights Protection and Human Welfare (Rospotrebnadzor)

Email: chub_ev@vector.nsc.ru

ORCID iD: 0000-0003-1521-897X

PhD, MD (Biology), Biology, head of department

Russian Federation, 630559, Novosibirsk Region, KoltsovoVladimir A. Ternovoi

State Scientific Center of Virology and Biotechnology “Vector” of the Federal Service for Surveillance of Consumer Rights Protection and Human Welfare (Rospotrebnadzor)

Email: tern@vector.nsc.ru

ORCID iD: 0000-0003-1275-171X

PhD, MD (Biology), head of the laboratory Department of Flavivirus Infections

Russian Federation, 630559, Novosibirsk Region, KoltsovoGalina V. Kochneva

State Scientific Center of Virology and Biotechnology “Vector” of the Federal Service for Surveillance of Consumer Rights Protection and Human Welfare (Rospotrebnadzor)

Email: kochneva@vector.nsc.ru

ORCID iD: 0000-0002-2420-0483

Doctor of Biology, head of the laboratory Department of Flavivirus Infections

Russian Federation, 630559, Novosibirsk Region, KoltsovoReferences

- Gonzalez V.D., Falconer K., Blom K.G., Reichard O., Mørn B., Laursen A.L., et al. High levels of chronic immune activation in the T-cell compartments of patients coinfected with hepatitis C virus and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and on highly active antiretroviral therapy are reverted by alpha interferon and ribavirin treatment. J. Virol. 2009; 83(21): 11407–11. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.01211-09

- Kovacs A., Karim R., Mack W.J., Xu J., Chen Z., Operskalski E., et al. Activation of CD8 T cells predicts progression of HIV infection in women coinfected with hepatitis C virus. J. Infect. Dis. 2010; 201(6): 823–34. https://doi.org/10.1086/650997

- Rauch A., James I., Pfafferott K., Nolan D., Klenerman P., Cheng W., et al. Divergent adaptation of hepatitis C virus genotypes 1 and 3 to human leukocyte antigen-restricted immune pressure. Hepatology. 2009; 50(4): 1017–29. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.23101

- Tengan F.M., Ibrahim K.Y., Dantas B.P., Manchiero C., Magri M.C, Bernando W.M. Seroprevalence of hepatitis C virus among people living with HIV/AIDS in Latin America and the Caribbean: a systematic review. BMC Infect. Dis. 2016; 16(1): 663. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-016-1988-y

- Zuckerman A.D., Douglas A., Whelchel K., Choi L., DeClercq J., Chastain C.A., et al. Pharmacologic management of HCV treatment in patients with HCV monoinfection vs. HIV/HCV coinfection: Does coinfection really matter? PLoS One. 2019; 14(11): e0225434. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0225434

- Cheng Z., Lin P., Cheng N. HBV/HIV coinfection: impact on the development and clinical treatment of liver diseases. Front. Med. (Lausanne). 2021; 8: 713981. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2021.713981

- Babu C.K., Suwansrinon K., Bren G.D., Badley A.D., Rizza S.A. HIV induces TRAIL sensitivity in hepatocytes. PLoS One. 2009; 4(2): e4623. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0004623

- Herbeuval J.P., Boasso A., Grivel J.C., Hardy A.W., Anderson S.A., Dolan M.J., et al. TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) in HIV-1-infected patients and its in vitro production by antigen-presenting cells. Blood. 2005; 105(6): 2458–64. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2004-08-3058

- Yu Y., Gong R., Mu Y., Chen Y., Zhu C., Sun Z., et al. Hepatitis B virus induces a novel inflammation network involving three inflammatory factors, IL-29, IL-8, and cyclooxygenase-2. J. Immunol. 2011; 187(9): 4844–60. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1100998

- Lara-Pezzi E., Gómez-Gaviro M.V., Gálvez B.G., Mira E., Iñiguez M.A., Fresno M., et al. The hepatitis B virus X protein promotes tumor cell invasion by inducing membrane-type matrix metalloproteinase-1 and cyclooxygenase2 expression. J. Clin. Investig. 2002; 110(12): 1831–8. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI15887

- Mohammed N.A., Abd El-Aleem S.A., El-Hafiz H.A., McMahon R.F. Distribution of constitutive (COX-1) and inducible (COX-2) cyclooxygenase in postviral human liver cirrhosis: a possible role for COX-2 in the pathogenesis of liver cirrhosis. J. Clin. Pathol. 2004; 57(4): 350–4. https://doi.org/10.1136/jcp.2003.012120

- Singh K.P., Crane M., Audsley J., Avihingsanon A., Sasadeusz J., Lewin S.R. HIV-hepatitis B virus coinfection: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and treatment. AIDS. 2017; 31(15): 2035–52. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000001574

- Brenchley J.M., Price D.A., Schacker T.W., Asher T.E., Silvestri G., Rao S., et al. Microbial translocation is a cause of systemic immune activation in chronic HIV infection. Nat. Med. 2006; 12(12): 1365–71. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm1511

- Qadir M.I. Hepatitis in AIDS patients. Rev. Med. Virol. 2018; 28(1). https://doi.org/10.1002/rmv.1956

- Sulkowski M.S. Viral hepatitis and HIV coinfection. J. Hepatol. 2008; 48(2): 353–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2007.11.009

- Kumar S., Stecher G., Li M., Knyaz C., Tamura K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018; 35(6): 1547–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msy096

- Titarenko R.V. Features of the drug situation and the problems of drug abuse prevention among Russian teenagers. Gumanitarnye, sotsial’no-ekonomicheskie i obshchestvennye nauki. 2015; (11-1): 191–4. (in Russian)

- Soboleva N.V., Karlsen A.A., Kozhanova T.V., Kichatova V.S., Klushkina V.V., Isaeva O.V., et al. The prevalence of the hepatitis C virus among the conditionally healthy population of the Russian Federation. Zhurnal infektologii. 2017; 9(2): 56–64. https://doi.org/10.22625/2072-6732-2017-9-2-56-64 (in Russian)

- Guntipalli P., Pakala R., Kumari Gara S., Ahmed F., Bhatnagar A., Endaya Coronel M.K., et al. Worldwide prevalence, genotype distribution and management of hepatitis C. Acta Gastroenterol. Belg. 2021; 84(4): 637–56. https://doi.org/10.51821/84.4.015.

- Olinger C.M., Lazouskaya N.V., Eremin V.F., Muller C.P. Multiple genotypes and subtypes of hepatitis B and C viruses in Belarus: similarities with Russia and western European influences. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2008; 14(6): 575–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.01988.x

- Isakov V., Tsyrkunov V., Nikityuk D. Is elimination of hepatitis C virus realistic by 2030: Eastern Europe. Liver Int. 2021; 41(Suppl. 1): 50–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.14836

- Rhodes T., Platt L., Maximova S., Koshkina E., Latishevskaya N., Hickman M., et al. Prevalence of HIV, hepatitis C and syphilis among injecting drug users in Russia: a multi-city study. Addiction. 2006; 101(2): 252–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01317.x

- Tsui J.I., Ko S.C., Krupitsky E., Lioznov D., Chaisson C.E., Gnatienko N., et al. Insights on the Russian HCV care cascade: minimal HCV treatment for HIV/HCV co-infected PWID in St. Petersburg. Hepatol. Med. Policy. 2016; 1: 13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41124-016-0020-x

- Rhodes T., Platt L., Judd A., Mikhailova L.A., Sarang A., Wallis N., et al. Hepatitis C virus infection, HIV co-infection, and associated risk among injecting drug users in Togliatti, Russia. Int. J. STD AIDS. 2005; 16(11): 749–54. https://doi.org/10.1258/095646205774763180

- Bobkova M.R., Samokhvalov E.I., Buravtsova E.V., Detkova N.V., Kravchenko A.V., Salamov G.G., et al. Hepatitis C among HIV-infected intravenous drug users in Russia. Mir virusnykh gepatitov. 2002; (6): 6–9. (in Russian)

- Aceijas C., Rhodes T. Global estimates of prevalence of HCV infection among injecting drug users. Int. J. Drug Policy. 2007; 18(5): 352–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2007.04.004

- Munir S., Saleem S., Idrees M., Tariq A., Butt S., Rauff B., et al. Hepatitis C treatment: current and future perspectives. Virol. J. 2010; 7: 296. https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-422X-7-296

- Zein N.N. Clinical significance of hepatitis C virus genotypes. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2000; 13(2): 223–35. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.13.2.223

- Probst A., Dang T., Bochud M., Egger M., Negro F., Bochud P.Y. Role of hepatitis C virus genotype 3 in liver fibrosis progression--a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Viral. Hepat. 2011; 18(11): 745–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2893.2011.01481.x

- Ramalho F. Hepatitis C virus infection and liver steatosis. Antiviral Res. 2003; 60(2): 125–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.antiviral.2003.08.007

- Esteban J.I., Sauleda S., Quer J. The changing epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection in Europe. J. Hepatol. 2008; 48(1): 148–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2007.07.033

- Shustov A.V., Kochneva G.V., Sivolobova G.F., Grazhdantseva A.A., Gavrilova I.V., Akinfeeva L.A. The occurrence of markers, the distribution of genotypes and risk factors for viral hepatitis C among some groups of the population of the Novosibirsk region. Zhurnal mikrobiologii, epidemiologii i immunobiologii. 2004; 71(5): 20–5. (in Russian)

- Schinazi R., Halfon P., Marcellin P., Asselah T. HCV direct-acting antiviral agents: the best interferon-free combinations. Liver Int. 2014; 34(Suppl. 1): 69–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.12423

- D’Ambrosio R., Degasperi E., Colombo M., Aghemo A. Direct-acting antivirals: the endgame for hepatitis C? Curr. Opin. Virol. 2017; 24: 31–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coviro.2017.03.017

- Feld J.J. Direct-acting antivirals for Hepatitis C Virus (HCV): The progress continues. Curr. Drug Targets. 2017; 18(7): 851–62. https://doi.org/10.2174/1389450116666150825111314

- Zhang Y., Cao Y., Zhang R., Zhang X., Lu H., Wu C., et al. Pre-existing HCV variants resistant to DAAs and their sensitivity to PegIFN/RBV in Chinese HCV genotype 1b patients. PLoS One. 2016; 11(11): e0165658. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0165658

- Palanisamy N., Kalaghatgi P., Akaberi D., Lundkvist Å., Chen Z.W., Hu P., et al. Worldwide prevalence of baseline resistance-associated polymorphisms and resistance mutations in HCV against current direct-acting antivirals. Antivir. Ther. 2018; 23(6): 485–93. https://doi.org/10.3851/IMP3237

- Ikeda H., Watanabe T., Shimizu H., Hiraishi T., Kaneko R., Baba T., et al. Efficacy of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir with or without ribavirin for 12 weeks in genotype 1b HCV patients previously treated with a nonstructural protein 5A inhibitor-containing regimen. Hepatol. Res. 2018; 48(10): 802–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/hepr.13074

- Wang G.P., Terrault N., Reeves J.D., Liu L., Li E., Zhao L., et al. Prevalence and impact of baseline resistance-associated substitutions on the efficacy of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir or simeprevir/sofosbuvir against GT1 HCV infection. Sci. Rep. 2018; 8(1): 3199. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-21303-2

- Kati W., Koev G., Irvin M., Beyer J., Liu Y., Krishnan P., et al. In vitro activity and resistance profile of dasabuvir, a nonnucleoside hepatitis C virus polymerase inhibitor. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015; 59(3): 1505–11. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.04619-14

- Di Maio V.C., Cento V., Lenci I., Aragri M., Rossi P., Barbaliscia S., et al. Multiclass HCV resistance to direct-acting antiviral failure in real-life patients advocates for tailored second-line therapies. Liver Int. 2017; 37(4): 514–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.13327

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Recommendations on Treatment of Hepatitis C 2018. J. Hepatol. 2018; 69(2): 461–511. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.026

- Popping S., Cento V., Seguin-Devaux C., Boucher C.A.B., de Salazar A., Heger E., et al. The European prevalence of resistance associated substitutions among direct acting antiviral failures. Viruses. 2022; 14(1): 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/v14010016

- Barth R.E., Huijgen Q., Tempelman H.A., Mudrikova T., Wensing A.M., Hoepelman A.I. Presence of occult HBV, but near absence of active HBV and HCV infections in people infected with HIV in rural South Africa. J. Med. Virol. 2011; 83(6): 929–34. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.22026

- Tramuto F., Maida C.M., Colomba G.M., Di Carlo P., Vitale F. Prevalence of occult hepatitis B virus infection in a cohort of HIV-positive patients resident in Sicily, Italy. Biomed. Res. Int. 2013; 2013: 859583. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/859583

- Laguno M., Larrousse M., Blanco J.L., Leon A., Milinkovic A., Martínez-Rebozler M., et al. Prevalence and clinical relevance of occult hepatitis B in the fibrosis progression and antiviral response to INF therapy in HIV-HCV-coinfected patients. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses. 2008; 24(4): 547–53. https://doi.org/10.1089/aid.2007.9994

- Panigrahi R., Majumder S., Gooptu M., Biswas A., Datta S., Chandra P.K., et al. Occult HBV infection among anti-HBc positive HIV-infected patients in apex referral centre, Eastern India. Ann. Hepatol. 2012; 11(6): 870–5.

- Hann HW., Gregory V.L., Dixon J.S., Barker R.F. A review of the one-year incidence of resistance to lamivudine in the treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Hepatol. Int. 2008; 2(4): 440–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12072-008-9105-y

- Elpaeva E.A., Pisareva M.M., Nikitina O.E., Kizhlo S.N., Grudinin M.P., Dudanova O.P. Role of hepatitis B virus mutant forms in progressive course of chronic hepatitis B. Uchenye zapiski Petrozavodskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta. 2014; (6): 41–6. (in Russian)

- Kozhanova T.V., Il’chenko L.Yu., Isaeva O.V., Alekseeva M.N., Saryglar A.A., Mironova N.I., et al. Circulation of hepatitis B virus variants carrying mutations in the polymerase gene among HBV-infected and HBV/HIV-coinfected patients. Sovremennye tekhnologii v meditsine. 2013; 5(2): 60–4. (in Russian)

- Isaeva O.V., Kyuregyan K.K. Viral hepatitis delta: an underestimated threat. Infektsionnye bolezni: novosti, mneniya, obuchenie. 2019; 8(2): 72–9. https://doi.org/10.24411/2305-3496-2019-12010 (in Russian)

Supplementary files